Real World De-Escalation

By Laszlo Madaras, MPH, MD, Chief Medical Officer, Migrant Clinicians Network

Tense situations do not only occur when a patient is angry or acting out. Sometimes, the clinician is upset. In this case, de-escalation needs to occur not just with a person the clinician is interacting with, but with the clinician as well. I work in an emergency room and COVID hospital ward, and every day I care for patients who could have been vaccinated against COVID-19, but chose not to. Some patients are very upset because they think we should be able to cure them. They are angry that the information we are providing about COVID-19 – that Ivermectin is not a proven cure, that the ICUs are full – does not match the misinformation that they had before they got sick. In their hospital room, as they lie dying of COVID, they ask for any help, any medicine or therapy that I can provide, to save their lives – when they had already forgone the vaccine, which is the best, safest, and proven method for keeping them out of the hospital and out of their current life-threatening condition.

In 2020, health care workers were hailed as heroes. But this year is different. These are challenging situations, and I have to admit that at times I am angry, too. Before a vaccine was available, it was easy to see all COVID-19 patients as innocent victims of a new virus that was killing patients worldwide. In 2021, with the possibility of a life-saving vaccine in much (but not all) parts of the world, I am angry that a patient, such as a life-long smoker with uncontrolled diabetes, did not get vaccinated, and now is in the ER with COVID-19. I am angry that they just assume we can “cure” them, when no cure exists, but an effective prevention tool – the vaccine – was purposely avoided. So, de-escalation in a time of COVID-19 has an extra dimension, because the health care provider is often overworked, traumatized, and, at times, angry.

When I find myself in a situation with a patient who is angry, I recognize that I need to take extra time, because my own situation, my own reactions to the patient, may not be viewed as level-headed. I take in the situation, check my own reactions, and try to back up, to start from a place of calm, as Dr. Weingarten says, so I can “high-road process” the information. After such situations, and in fact throughout this COVID pandemic, self-care is much needed. Time to decompress, to process what occurred, and to return to a healthy state in my body and mind is critical.

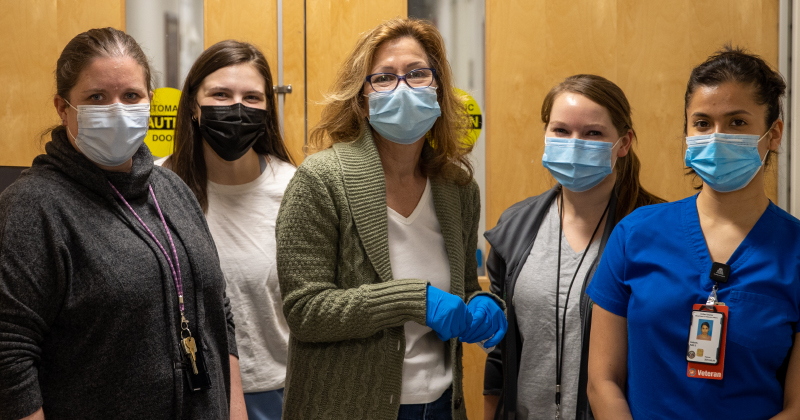

Recently, at a shopping mall in an urban city, three community outreach workers were standing near a table that had a colorful tri-fold with helpful, local information about how to get a vaccine for COVID-19. They had had several pleasant exchanges when a man in his thirties approached the table looking tense and agitated. The man was clearly upset and he used his right hand to point at the three people at the table, while using his left hand to swipe several of the information sheets off the table. The workers, all women, froze momentarily and then calmly asked him to step aside. In this instance, he did. After he was a far distance away, out of earshot, the three women looked at each other and, trembling, they began to shake their heads and release a kind of strangled laughter, more tension release than humor.

Sadly, this is not an uncommon scenario. It is an unfortunate sign of our times that episodes like the one above occur routinely and provide the raison d’etre for the topic of this article: how to de-escalate an interaction that has become hostile and aggressive. In the course of service to the community, health care workers are increasingly encountering people who need help but rebuff or reject it. In some instances, the behavior that health care workers are facing is threatening, violating, and violent. This is clearly intolerable, indefensible, and infuriating.

This article presents ideas about how to de-escalate interactions that have become tense while taking a firm position that safety comes first. That is, empathy can wait if personal safety is at risk. At the same time, it is useful to have some understanding of what might be going on for someone who turns against a health care worker who is trying to help. The second part of the article is not meant to justify harassing behavior but only to put forward some ideas as to why it might be happening. It is an effort to place an individual’s negative behavior in a wider cultural context of the particular socio-historical, polarized moment we are living through.

- Watch for your body’s warning signs: Whether or not you are the person being harassed or you are a witness to it, the situation will likely be jarring for you. Most of us “send” consistent physical and emotional signals when we are upset, even if we remain calm. Physical cues might be that our neck flushes, a knot forms in our stomach, or our heart races. Emotionally, we may feel numb, agitated, or afraid. It is important to notice the signals our bodies send and recognize them as a warning that we are in an interaction that is uncomfortable or even unsafe.

- Exit hostile situations: Some negative interactions cannot be salvaged. It is important to distinguish between someone who is upset and “triggered” but still able to engage in a respectful conversation, and someone who has become hostile and aggressive. In a setting where there are many other staff, this is the time to move away and notify other team members. If you are out in the field, whether you are alone or with one other person, this is a situation to leave. This is exactly the kind of situation in which the expression, “Empathy can wait” needs to apply.

- Look for worsening behavior: If you are encountering someone who strongly disagrees with what you are saying but they are fairly calm and still respectful, look for signs as you proceed in your interaction that things are turning negative, that is, their behavior looks more, not less, dysregulated. Signs might be: the person’s fists are clenched; they are talking very loudly or very quietly; they appear confused; or their speech is rapid. These are signs that you probably need to end the interaction.

- De-escalating in a safe situation: If you deem the interaction safe to continue, and believe it will result in a rational exchange, here are some tips that can help continue to de-escalate negative behavior:

- Maintain a safe distance, creating at least three feet of distance between you and the other person so that each of you has a demarcated personal space.

- Attend to what the person is trying to say about their experience. Do not make a negative judgmental statement.

- Keep your non-verbal communication --your tone of voice, gestures, facial expressions --as neutral as possible.

- If it feels safe, ignore verbal challenges and try to answer what seems to be of most concern to the person; “Ignore the challenge but not the person.”1

- Allow pauses and even silence, for the person may need these to make sense of what you are saying.

These five tips are suggestions for techniques that may de-escalate negative interactions. Each person will develop their own strategies for what works best for them through a trial-and-error process. Above all, your mantra needs to be: “I need to be safe.”

Given that we are placing safety first, it still is possible to take a moment to consider what might make or turn an interaction negative. Our time is one in which there is deep polarization in our country. Behaviors and opinions have become divided. Aspects of health care itself have lost their neutrality and become “signs” of beliefs. In this climate, if you hold a different perspective about a health care measure from the person you are talking to, your perspective may “trigger” a dysregulated response.

All of us have emotional responses to some interactions. At best, we maintain our ability for our emotions to be integrated with our rational thought process, what is called “high-road processing.” If someone is triggered by what we say and it elicits a threat response, that person may be having an emotional response that bypasses their rational thought process. They are using “low road processing,” an “evolutionary conserved direct emotional pathway designed to protect individuals from life-threatening danger, and is designed to elicit defensive responses without conscious thought.”2 It may be very difficult to calm the person down in time to “turn on” their “high-road processing.” That is when it is best to leave.

After a difficult exchange three things are imperative:

- Ground yourself: Everyone should have one or two surefire ways to self-sooth that require no special tools or devices, that are simple and always at hand. It might be singing at the top of your lungs, a minute of deep breathing, or counting backwards by three.

- De-brief: Tell someone about what happened. If someone was there with you, discuss what went wrong, what it felt like to you, and what might improve a next encounter.

- Take care of yourself: Know how you are going to practice self-compassion and self-care. There are resources below that may be helpful to you.

Resources

- What About YOU?: A Workbook for those who care for others: http://508.center4si.com/SelfCareforCareGivers.pdf

- The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook: A proven way to accept yourself, build inner strength, and thrive. Kristen Neff and Christopher K. Germer, Ny: NY: Guilford Press, 2018

- Five Easy Pieces to De-Stress: https://www.migrantclinician.org/blog/2020/nov/five-friday-reducing-anxiety-and-stress.html

References

1 Crisis Prevention Institute. CPI’s Top 10 De-Escalation Tips. 15 October 2020. Available at: https://www.crisisprevention.com/Blog/CPI-s-Top-10-De-Escalation-Tips-Revisited

2 Nehrenberg D. Emotional low road high road. Available at: https://sites.google.com/site/evopsyc/home/emotion/emotional-low-road-high-road

Read this article in the Fall 2021 issue of Streamline here!

Sign up for our eNewsletter to receive bimonthly news from MCN, including announcements of the next Streamline.