Toxic Stress

[Editor’s Note: This blog post comes from MCN Board Member Eva Galvez, MD, a family physician at Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center, a Community Health Center based in Hillsboro, Oregon.]

Earlier this week, I saw a patient for her prenatal visit. She is now in her 20th week of pregnancy. Her husband was deported during her tenth week of pregnancy and her seven-year-old son has been having behavioral challenges since his father was deported. What do I need to think about for this infant’s first months of life? What impact will stress have on her early formative years? What does the mother need to support her through the next phase of her life?

Last week, I had the great honor of participating on the panel for Virginia Garcia’s 10th Annual Health Care Symposium on Toxic Stress. This symposium was a wonderful opportunity to join with health professionals from other fields to examine the impact of toxic stress and to discuss ways in which we as clinicians can reduce the impact that toxic stress has on our patients’ lives.

As the daughter of seasonal agricultural workers, I was raised in a tight-knit community of family and friends, most of whom were seasonal and mobile agricultural workers from Mexico. I grew up listening to stories from my parents, friends, and family about growing up in poverty and the suffering endured as a result of their economic hardships. As a teenager, these stories generated a deep desire to provide my community with empathy, hope, and healing, and led me to pursue a career in medicine. Now as a practicing physician, I do my best to provide my patients with the comfort and healing that I always dreamed of.

Despite my work to provide my patients high-quality, culturally competent health care, many of patients continue to face the burden of poor health and chronic disease. I have discovered that despite overcoming some of the economic hardships, there are other challenges that are faced by my patients. Experiences of racism, discrimination, social isolation, violence, and fear of deportation have led to other problems such as depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, domestic abuse, and family dysfunction.

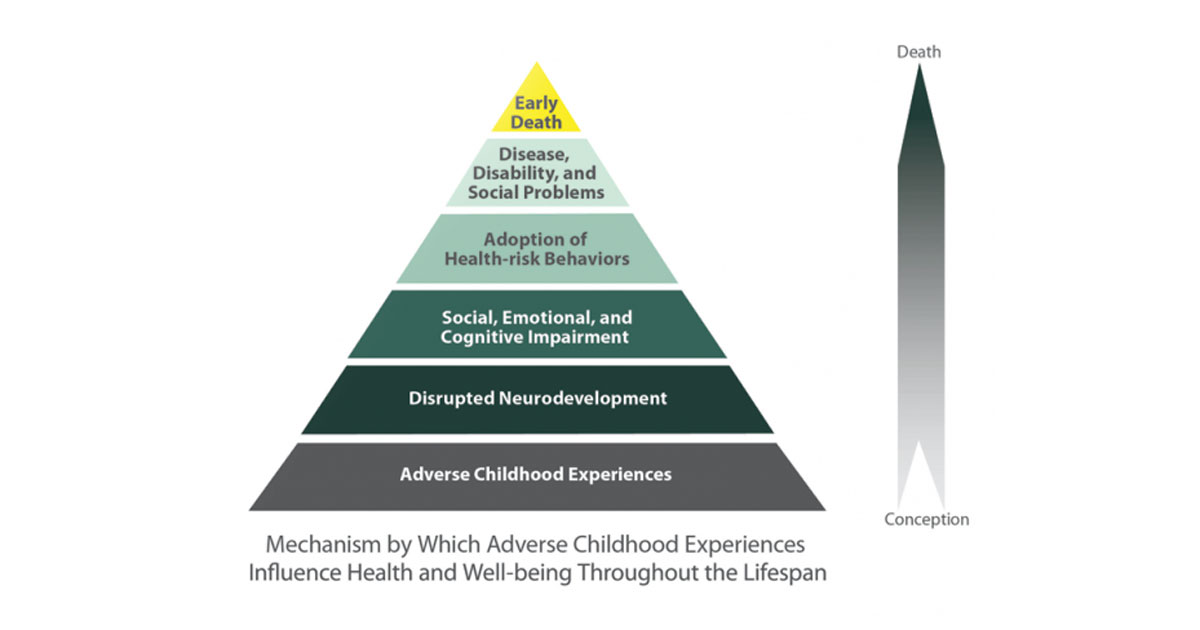

This past year, I had the wonderful opportunity to learn about ACE, or “adverse childhood experiences.” ACE research shows that persistent high levels of adversity, especially early in life, not only increases the risk of mental health and substance use disorders, but also negatively impacts physical health. Patients with high ACE scores have an increased risk for serious health problems such as as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. In fact, research on adverse childhood events shows that patients with high levels of adversity have a life expectancy of 20 years shorter than those without these challenges.

ACE Pyramid representing conceptual framework for the ACE Study. Graphic: cdc.gov.

At the Health Care Symposium, there was consensus that early recognition and treatment of toxic stress are needed in order to reduce the long term health effects, but there was also acknowledgement that there is a need to examine those factors that are protective and that promote resilience within families.

As I learn more about the connection between toxic stress and health, I have begun to explore how, as a clinician, I might be able to mitigate the effects that toxic stress has on my patients’ lives. As with most diseases in medicine, prevention and early identification are key.

That’s why I have learned to adjust my strategies, to better serve my patients like my pregnant patient I saw this week. I know that she is struggling with significant amounts of stress and, as the family’s physician, I am already well aware of the adversity that her newborn will face even before the infant arrives at my office for his or her first well-child check. This unique perspective allows me to intervene before the toxic stress sets in motion a chain of events that has the potential to lead to serious health problems. I have already taken the first step in intervening by educating my patient regarding the potential impact of adversity on her child’s health. As I continue to care for her through her pregnancy and beyond, I plan to ensure that she has access to counseling and community programs that will promote her physical and emotional well being as a healthy parent is a key factor in promoting resilience among children, even when exposed to high levels of adversity.

However, we don’t always have the privilege to be so familiar with our patients; therefore, I believe we need to advocate for universal screening for toxic stress during our routine clinic visits. Currently, our training focuses on diagnosis and treatment. We learn to quickly sift through information in order to narrow down our diagnosis and provide a treatment plan. However, we need the time and training to listen to the story on the surface and the story underneath. I believe that when we begin to really understand the underlying challenges, then we can begin to take the first steps in providing effective treatment plans.

But we need training that goes beyond just identification of toxic stress. We need to arm our clinicians with tools and brief clinical interventions that we can use during our routine clinic visits. It is my experience that even when a robust network of support services is readily available, many of our patients will never fully engage in these services. Nevertheless, our patients will continue to seek out primary care clinicians for their routine medical concerns. Mixed in with their health problems will be stories of ongoing stress and adversity. If we are truly committed to helping our patients heal, we must prepare our frontline clinicians with tools that will begin the process of treating the underlying issues.

We must acknowledge that ongoing exposure to suffering and adversity may take a toll on our own physical and mental well-being. Therefore, as we advocate for additional clinician training, we must also advocate for a health care system that supports clinician self care and wellness. I believe that investing the time to care for ourselves will prevent burnout and ultimately cultivate more empathetic and compassionate clinicians.

Making these changes to our health care system requires more than just a handful of clinicians or a few health center organizations. As a medical community we need to advocate for these changes on a systemic level. We must also advocate for changes in the way we reimburse clinicians.

I once heard someone say that clinicians are witnesses of great injustices, but I believe that we are also witnesses of great stories of hope and resilience. We must must shine a light on these stories in order to promote awareness regarding the profound connection between toxic stress and adverse health. Through the telling of these collective stories, we can begin to find solutions to mitigate the long-term risks of toxic stress, eventually leading to healthier individuals and communities.

Visit centerforyouthwellness.org for their downloadable ACE questionnaire and user guide.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.

- Log in to post comments