How to De-Escalate a Tense Interaction

[Editor’s Note: The Fall 2021 issue of Streamline is now arriving at mailboxes – yes, those physical boxes that receive paper – across the country! You can read the entire issue, which features articles on climate change, marginalized worker health, farmworker mental health, and more, here. Here’s one of the articles from this issue, edited for the MCN blog. Watch our social media in the coming weeks for a video accompaniment on this same topic.]

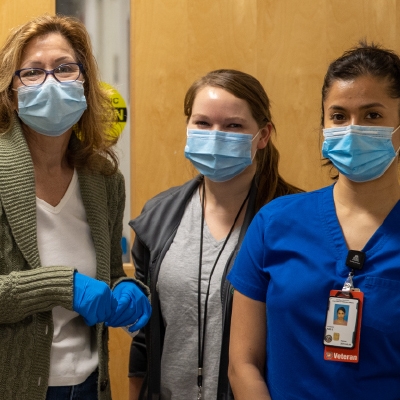

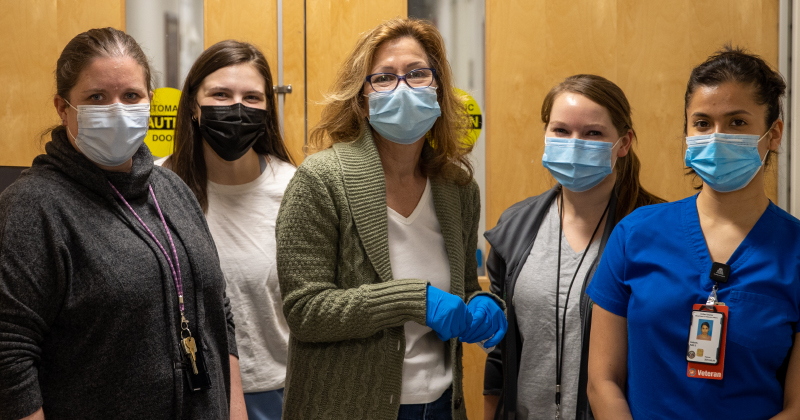

Recently, at a shopping mall in an urban city, three community outreach workers were standing near a table that had a colorful tri-fold with helpful, local information about how to get a vaccine for COVID-19. They had had several pleasant exchanges when a thirty-something, heavy-set man approached the table looking tense and agitated. The man was clearly upset and he used his right hand to point at the three people at the table, while using his left hand to swipe several of the information sheets off the table. The workers, all women, froze momentarily and then calmly asked him to step aside. In this instance, he did. After he was a far distance away, out of earshot, the three women looked at each other and trembling, they began to shake their heads and release a kind of strangled laughter, more tension release than humor.

Sadly, this is not an uncommon scenario anymore. It is an unfortunate sign of our times that episodes like the one above occur routinely and provide the rationale for addressing the topic of this article: how to de-escalate an interaction that has become hostile and aggressive. In the course of service to the community, health care workers are increasingly encountering people who need help but rebuff or reject it. In some instances, the behavior that health care workers are facing is threatening, violating and violent. This is clearly intolerable, indefensible and infuriating.

I present ideas about how to de-escalate interactions that have become tense while taking a firm position that safety comes first. That is, empathy can wait. At the same time, it is useful to have some understanding of what might be going on for someone who turns against a health care worker who is patently trying to help. The second part of the article is not meant to justify harassing behavior but only to put forward some ideas as to why it might be happening. It is an effort to place an individual’s negative behavior in a wider cultural context of this polarized moment we are living through.

- Whether or not you are the person being harassed or you are a witness to it, it will likely be jarring for you. Most of us “send” consistent physical and emotional signals when we are upset, even if we remain calm. Physical cues might be that our neck flushes, a knot forms in our stomach, or our heart races. Emotionally, we may feel numb or agitated or afraid. It is important to recognize the signals we send and use them as a warning that we are in an interaction that is uncomfortable or even unsafe.

- Some negative interactions cannot be salvaged. It is important to distinguish between someone who is upset and “triggered” but still able to engage in a respectful conversation and someone who has become hostile and aggressive. In a setting where there are many other staff, this is the time to move away and notify other team members. If you are out in the field, whether you are alone or with one other person, this is a situation to leave. This is exactly the kind of situation in which the expression “empathy can wait” needs to apply.

- If you are encountering someone who shows signs that they are having trouble hearing what you are saying, but they are fairly calm and still respectful, look for signs as you proceed in your interaction that things are getting worse not better. That is, their behavior looks more not less dysregulated. Signs might be: the person’s fists are clenched, they are talking very loudly or very quietly, they appear confused, or their speech is rapid. These are signs that you probably need to end the interaction.

- If the interaction seems to be turning around into a more rational exchange, here are some tips that can help continue to de-escalate negative behavior:

a. Maintain a safe distance, creating at least three feet of distance between you and the other person so that each of you has a demarcated personal space.

b. Attend to what the person is trying to say about their experience. Do not make a negative judgmental statement.

c. Keep your non-verbal communication --your tone of voice, gestures, facial expressions --as neutral as possible

d. If it feels safe, ignore verbal challenges and try to answer what seems to be of most concern to the person. “Ignore the challenge but not the person.”1

e. Allow pauses and even silence to give the person time to make sense of what you are saying.

These five tips are suggestions for techniques that may de-escalate negative interactions. Each person will develop their own strategies for what works best for them through a trial and error process. Above all, your mantra needs to be: “I need to be safe.”

Given that we are placing safety first, it still is possible to take a moment to consider what might make or turn an interaction negative. There is deep polarization in our country. Behaviors and opinions have become divided into black and white categories, often pro-this or con-that. Aspects of health care itself have lost their neutrality and become “signs” of beliefs. In this climate, if you hold a different perspective about a health care measure from the person you are talking to, your perspective may “trigger” a dys-regulated response.

All of us have emotional responses to some content. At best, we maintain our ability to integrate our emotions with our rational thought process, what is called “high-road

processing.” If someone is triggered by what we say and it elicits a threat response, that person may be having an emotional response that bypasses their rational thought process. They are using “low road processing,” an “evolutionary conserved direct emotional pathway designed to protect individuals from life-threatening danger and is designed to elicit defensive responses without conscious thought.”2 It may be very difficult to calm the person down in time to “turn on” their “high-road processing.” That is when it is best to leave.

After a difficult exchange three things are imperative:

- Ground yourself: Everyone should have one or two surefire ways to self-sooth that require no special tools or devices, that are simple and always at hand. It might be singing at the top of your lungs, a minute of deep breathing or counting backwards by three.

- De-brief: Tell someone about what happened. If someone was there with you, discuss what went wrong, what it felt like to you and what might improve a next encounter.

- Take care of yourself: Know how you are going to practice self-compassion and self-care. There are resources below that may be helpful to you.

Resources:

- What About YOU?: A Workbook for those who care for others: http://508.center4si.com/SelfCareforCareGivers.pdf

- The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook: A proven way to accept yourself, build inner strength, and thrive. Kristen Neff and Christopher K. Germer, Ny: NY: Guilford Press, 2018

- Five Easy Pieces to De-Stress: https://www.migrantclinician.org/blog/2020/nov/five-friday-reducing-anxiety-and-stress.html

1 https://www.crisisprevention.com/Blog/CPI-s-Top-10-De-Escalation-Tips-Revisited

2 https://sites.google.com/site/evopsyc/home/emotion/emotional-low-road-high-road

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.

- Log in to post comments