The Children Left Behind: In Honduras, Dr. Laszlo Madaras Encounters Fractured Families in the Wake of Migration to US

Raquel is traveling alone with her two-year-old daughter, hoping soon to live with her sister and brother-in-law in the US. She is pregnant and was traveling with the father of the toddler, but they were separated by US Customs and Border Protection, so she is continuing on her own. She and her partner fled the violence in her home country. She left her two older children with their grandparents in rural Honduras with hopes of one day reuniting the family...

Having closed several hundred prenatal cases with MCN's Health Network (HN) program, I have read about many such cases of young women, often with their partners, leaving some of their older children behind with a grandparent until they could later send for them. HN offers mobile international case management and psychosocial support to many types of patients including pregnant people migrating to the US. Their stories are recorded in their health chart on one, maybe two, pieces of paper which nevertheless contain powerful stories of migration due to drug gang violence, extortion, sexual trauma, hardship, family separation that risks becoming a long-term separation, and more. I am always amazed by the persistence and endurance of such young women who would risk everything to protect and improve the lives of their children.

In February, I had a chance to work again in a rural part of Honduras, where I have provided primary care with a medical team for several weeks every few years, for decades. Much of the children’s health care was provided at the local health center where their grandmother or grandfather brought them. As part of intake, I interview some of the grandparents and the children left behind in their care while the "middle generation" finds work in a safer environment than the one they left in their home country.

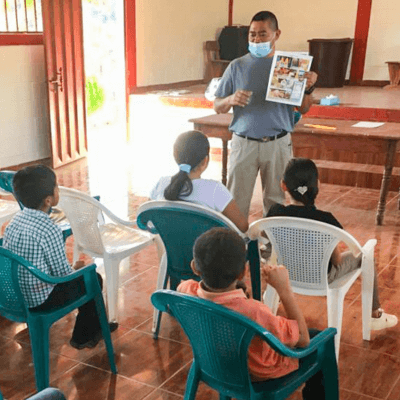

We also visited children in grades one through six, as they were attending classes. We brought toothbrushes and comic books in basic Spanish on dental care and healthy meals to prevent tooth decay. Like in the clinic, we discovered that many of them were being raised by adults other than their biological parents.

There are some unintended consequences to this type of family break-up, with some parents missing large portions of their children's upbringing, and grandparents who may have already spent much of their more energetic years raising their own children now taking on the upbringing of their grandchildren. While these situations are not new in the history of human migration, it is worth exploring some of the challenges that arise.

Some may not have seen their parents for months or even years. Some were with other relatives as many grandparents had succumbed to COVID-19 during the pandemic before vaccines became available (which occurred at a much later date in Honduras than in the US). Some of the children were showing signs of depression but many appeared happy and very involved with their school friends and teachers. There were variations in grandparental discipline – either more or much less than the parents would provide depending on the grandparent’s child-rearing style. The full impact on family life and the changes that have occurred in these children may not be fully realized until they are older.

While I have traveled and worked in Honduras many times since 2002, I realize my experiences cannot be generalized to all children and families in all of Honduras. Nevertheless, in this microcosm, I can see the impact of migration as parents leave their home countries either due to political instability, gang violence, climate change, or other reasons to seek a better life elsewhere, and the impact this has on the children left behind.

Learn more about conditions for pregnant people at the border:

- Annie Leone wrote about her work providing prenatal care at the US-Mexico border in coordination with Health Network: Devastating Separations Continue for Families Seeking Asylum, with Dire Health Consequences

- Read MCN’s white paper, which includes case studies from Health Network prenatal patients: Failures of US Health Care System for Pregnant Asylum Seekers

- Read MCN’s Deliana Garcia, on the white paper: Despite Legal Status, Pregnant Asylum Seekers Can’t Get Prenatal Care in our Overextended Health System

- Log in to post comments